This proposal deals with water resources management and the role of law in achieving sustainable development and building cooperation between countries sharing transboundary water resources. As the UN Secretary-General Ban Ki-Moon, has stated at Davos 2010 “the water problem is broad and systemic. Our work to deal with it must be so as well “.This is equally true for water resources management and water services delivery. The single discipline or sector model – using only hydrology, only engineering, only law or only economics to address the world’s water problems – is no longer tenable. Interdisciplinary approaches are needed, led by a constituency of new talent – eco-hydrologists, engineers and economists who understand water law and vice versa, in creative partnerships encouraging dialogue across sectors. An interdisciplinary approach is at the heart of the UNESCO Centre’s teaching and research, and is central to all the executive training undertaken under the Water Law Water Leaders international water law tuition and mentoring; Water Law Water Leaders is all about developing at basin-level the capacity of a new generation of water leaders to meet the challenges of the twenty-first century through helping to empower them to achieve the best possible long-term results for their river basins on their return.

International water law adopts the primary substantive principle of “equitable and reasonable utilization”, as embedded in the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention (UN Watercourses 1997, Wouters 1999a). This rule of law operates at two levels: setting the standard to be achieved, and, establishing the operational approach to determine that standard. Thus, a new or increased use of transboundry waters is “lawful” where it is determined to be “equitable and reasonable”. Whether or not a use qualifies as being “equitable and reasonable” is determined on a case by case basis: “all relevant factors are to be considered together and a conclusion reached on the basis of the whole” (Art. 6(3) UN Watercourses Convention). This means that, consistent with integrated water resource management, States must take into account the interrelatedness of freshwater bodies, sectoral integration and multi-interest considerations. While the notion of equity requires that these issues be reconciled, the notion of reasonableness implies a certain standard on how a transboundry watercourse is utilized. Given our present knowledge of the effects of economic development on the environment, it is extremely unlikely that a use, which endangers the long-term potential of renewable resources such as water, would be considered reasonable (Wouters 1999b).

The Role of International Water Law in Promoting Sustainable Development Numerous global policy documents identify and promote the concept of sustainable development (UN CSD 2001, World Water Vision 2000, UN CSD 1998, Agenda 21 1992, Dublin Statement 1992). The message common to each of these instruments is that sustainable development is integrally linked with the pursuit of an integrated water resource management strategy. Integrated water resource management requires water resources to be managed as a finite and vulnerable resource, an economic good, and a natural resource (Dublin Statement 1992). Such integration occurs at three levels: interrelated freshwater bodies should be managed as a unit (the catchment area being the most appropriate level); there should be multi-sectoral integration (technological, economic, social, environmental, and human health considerations); and multi-interest in the use of water resources must be given due consideration. Furthermore, a strategy for the sustainable development must ensure sufficient access to safe water and adequate sanitation for all, along with the protection of aquatic ecosystems. However, attempts to achieve such policy objectives often result in conflicts of uses: in many cases there is insufficient water, in quality and / or quantity, to meet all competing needs.

The primary purpose of a legal regime is to establish a coherent framework of enforceable rights and obligations, which ensure predictability and further common goals (Geneva Strategy on Compliance). For international water law to be consistent with, and promote, the goal of sustainable development, as outlined above, it must comprise a set of rights and obligations that regulate the use of freshwater resources so as to preserve their availability for both present and future generations; while also giving priority to the special needs of the poor (DFID 2001 Water Crisis Strategy). How does international water law do this? International water law adopts the primary substantive principle of “equitable and reasonable utilization”, as embedded in the 1997 UN Watercourses Convention (UN Watercourses 1997, Wouters 1999a). This rule of law operates at two levels: setting the standard to be achieved, and, establishing the operational approach to determine that standard. Thus, a new or increased use of transboundry waters is “lawful” where it is determined to be “equitable and reasonable“. Whether or not a use qualifies as being “equitable and reasonable” is determined on a case by case basis: “all relevant factors are to be considered together and a conclusion reached on the basis of the whole” (Art. 6(3) UN Watercourses Convention).

This means that, consistent with integrated water resource management, states must take into account the interrelatedness of freshwater bodies, sectoral integration and multi-interest considerations. While the notion of equity requires that these issues be reconciled, the notion of reasonableness implies a certain standard on how a transboundry watercourse is utilized. Given our present knowledge of the effects of economic development on the environment, it is extremely unlikely that a use, which endangers the long-term potential of renewable resources such as water, would be considered reasonable (Wouters 1999b). Finally, in line with the promotion of sustainable development, the principle of equitable and reasonable use requires The Role of International Water Law in Promoting Sustainable Development that in reconciling competing uses of transboundry watercourses, “special regard” must be given to “vital human needs” (Article 10(2), UN Watercourses Convention 1997).

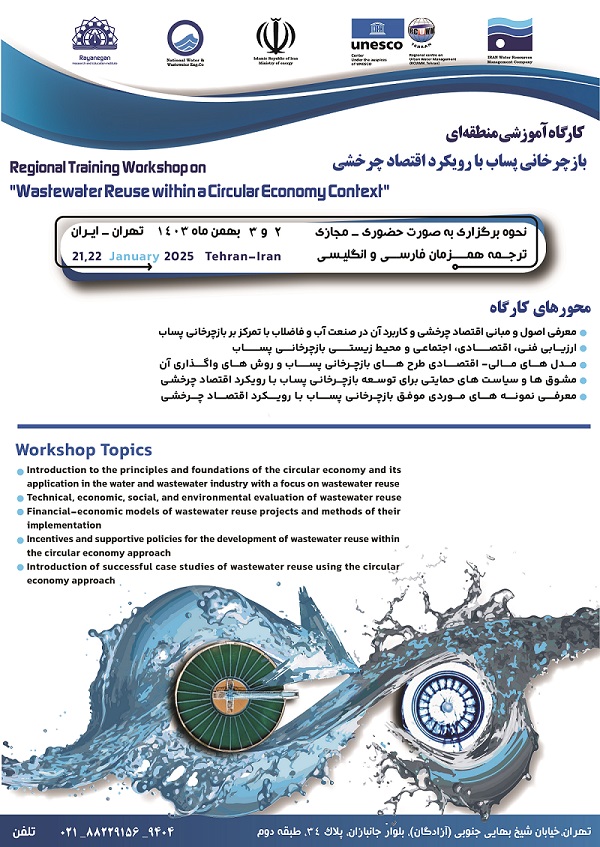

Objectives

The main goal of this event is capacity development and the target group would be managers, decision makers and experts involved in water resources management. During this workshop, general information on water laws by considering the participants level will be presented.

The expected outcome would be to enable the participants to promote their knowledge and apply these laws in their own countries by taking into account the requirements.